ATCHISON, Kan. (CN) — The project that may have found Amelia Earhart’s long-lost plane at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean began with a father and son magnet fishing off a dock in Charleston, South Carolina, during the Covid pandemic.

Tony Romeo and his son Stuart, age 5 at the time, pulled up a pair of scissors. Stuart asked what else could be at the bottom of the ocean. And Tony Romeo thought of Amelia Earhart and her airplane that disappeared in 1937.

“That just prompted a lot of thinking,” Romeo said. “Everything that goes down in the ocean is a story.”

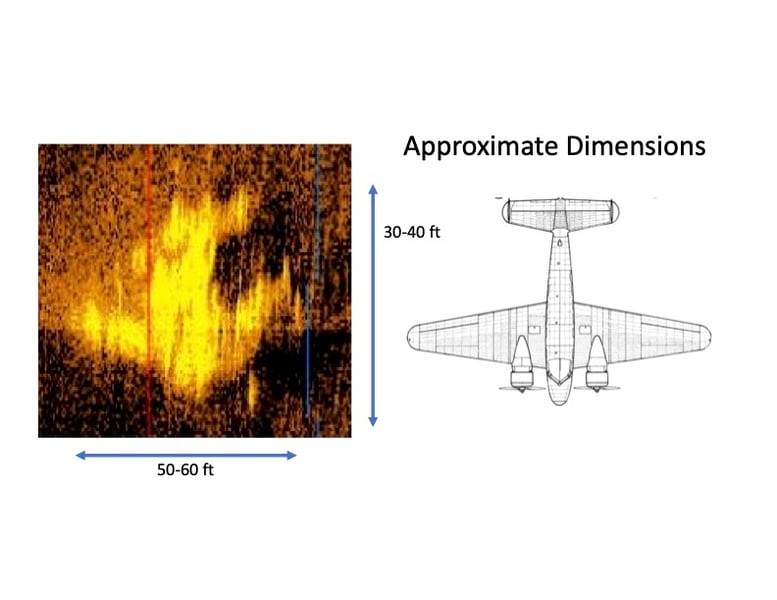

In 2023, Romeo and other explorers from his Deep Sea Vision marine robotics company used an underwater drone to record a sonar image from the bottom of the ocean floor shaped similar to the twin-engine Lockheed Electra piloted by Earhart that disappeared during an attempt by Earhart and navigator Fred Noonan to circumnavigate the globe.

Romeo and his brother Lloyd Romeo appeared on a panel Friday in Atchison called “Adventure Amelia: A Conversation With Explorers In The Search For Amelia Earhart.” The event took place during the annual Amelia Earhart Festival in her hometown of Atchison, a city of more than 10,000 overlooking the Missouri River in northeast Kansas.

In addition to the Romeo brothers, the panel included Liz Smith, developer of the theory of Earhart and Noonan’s disappearance that Deep Sea Vision utilized in their search of the ocean floor, plus two others who had worked on other searches for the Electra: Gary LaPook, navigation consultant with The Stratus Project and Rod Blocksome, a radio communication expert with Nauticos Corporation.

The panel took place at the Fox Theater in downtown Atchison, where the famed aviator was born in 1897. The town’s attractions include the Amelia Earhart Birthplace Museum and the Amelia Earhart Hanger Museum, which hosted Friday’s event.

“It’s still a mystery. We don’t know what happened in those last hours. But these folks are working on it,” said Dorothy Cochrane, a curator in the aeronautics department at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, who moderated the panel.

While there was sharp if civil disagreement among some on the panel about what may have led to the crash, they seemed to agree the image found by Deep Sea Vision was compelling. Blacksome said he had previously found images at the bottom of the ocean he thought might be Earhart’s airplane, but weren’t.

“Your image, it could be the airplane. For your sake I hope it is,” said Blacksome. “I think it’s the most interesting target that’s shown up, even compared to the ones we’ve had. So my hat’s off to you.”

And while there is a significant possibility the image may not end up being Earhart’s plane, the effort was not wasted because they will know more about where the Electra isn’t. It’s out there, somewhere.

“Now we know a whole lot about where it’s not,” Blacksome said. “It does narrow down the possibilities.”

Said Smith: “It’s not about whether you’re right or wrong. It’s are you contributing so we can find her.”

Earhart and Noonan disappeared flying the twin-engine Lockheed Electra 10-E after leaving Lae, New Guinea, on July 2, 1937, on their way to Howland Island in the central Pacific, just north of the equator and east of the international dateline.

The pair were on an equatorial circumnavigation route, making the voyage uniquely difficult in terms of distance and finding places to land safely — particularly over the vast expanse of the Pacific.

Clik here to view.

Despite the most expensive air and sea search in American history to that point, Earhart and Noonan were never found, creating one of the most enduring mysteries of early aviation.

Confirmation or refutation of the find is likely years away; the wreckage is suspected to rest roughly 4,000 feet deeper than the remains of the Titanic.

The Romeo brothers both obtained private pilot licenses at young ages. Tony Romeo, Deep Sea Vision’s CEO, is a 2002 Air Force Academy graduate and a former Air Force intelligence officer who had founded a tech company later acquired by Zillow, then went to law school, and then got involved in real estate. He was looking to do something more adventurous.

After he returned from magnet fishing Romeo called older brother Lloyd, an engineer nearing retirement, who said he believed the Electra would probably be found by someone in the next 5 to 10 years. The brothers decided it might as well be them.

“At first … this was just hypothetical talk, but then it was like, let’s look at the equipment that can actually do this,” Lloyd Romeo, project manager for Deep Sea Vision, said in an interview.

For the Romeo brothers, the search was personal. Their father was a longtime pilot for Pan-Am. Noonan had planned many of the airline’s routes, and their father probably knew people who would have known the esteemed navigator. The brothers started researching the disappearance.

Deep Sea Vision surveys seabeds in deep parts of the oceans. Commercial work, like cable surveys, helps fund the Earhart search.

“There are a lot of ways to make money, but this one seemed … like the most interesting way,” Tony Romeo said.

For equipment, they settled on a 24-foot-long drone, a Hugin 6000. One of three private companies who employ it, Tony Romeo had to run a gauntlet of red tape to get U.S. government authorization to use the machine, which can also be used for military purposes.

“It’s basically an underwater Tesla,” said Lloyd Romeo, project manager for Deep Sea Vision.

They put together a team, got a 111-foot vessel and headed out to the central Pacific to the area of Howland Island, where existing evidence suggested was the most likely location of the wreckage.

They laid out a map etched with boxes. When they were done searching a square they would fill it in with a yellow highlighter.

They based their search in part on Smith’s Date Line Theory, which posits that Earhart and Noonan crossing the International Date Line confused Noonan’s navigation, possibly causing the pair to miss the island.

It took 90 minutes for the drone to travel to the bottom of the ocean and an equal amount of time to surface, giving it 33 hours at the bottom to search, Lloyd Romeo said. The data was stored in a canister on board the drone.

Their vessel was forced to stay at least three miles away from Howland Island, which is now a bird sanctuary.

They were out there 90 days but didn’t find anything. Demoralized, after they departed the area and were en route to Samoa when a sonar engineer pulled some images from a corrupted file. And there it was, the grainy image in the shape similar to that of a Depression-era Lockheed Electra from roughly 60 miles west of Howland Island.

“We were looking at it like, wow! That’s got to be it,” Lloyd Romeo said. “It definitely changed the attitude on the boat.”

The odds of it being Earhart’s aircraft are difficult to pin down, but he estimates it at 85%.

“There’s certainly room for skepticism here,” he said. “Nothing should be taken for granted.”

Tony Romeo said he “100%” wants to raise the Electra to the surface. Holding a model in his hand, he indicated where the key joints would be. If they are still strong, it should come up nicely, he said. “I don’t want to lose one rivet of this thing.”

The remains of Earhart and Noonan could still be in the aircraft. If they are, he believes the appropriate thing would be to bring them home to the United States for proper burials. He said it was like returning service members who had died overseas at war. In Earhart’s case, he thought it appropriate to return her to Atchison.

“This is her hometown,” Tony Romero told the audience at the Fox Theater on Friday. “She needs to come home. If I were her, I would want to come home.”

Pook said he was skeptical of Date Line Theory. He has Noonan’s chartwork from other flights and he had used Greenwich Mean Time. “So you are not going to jump forward a whole day,” he said.

But Tony Romeo pointed out that it was a time-zone issue. Howland Island had its own time zone — a half hour off an adjoining time zone. And Noonan was 30 minutes off on his reports to the Itasca.

“Somewhere he had missed his time. He knew that they were off. There was a 30-minute problem there for them,” he said to Pook. “You’re shaking your head, but they were reporting at the wrong time.”

The festival itself takes place Friday and Saturday. Country music band Diamond Rio is scheduled to take the stage at the waterfront Friday night and a host of other activities are planned. On Saturday, the museum is hosting another event featuring the Romeo brothers.

Toward the end of the panel, Tony Romeo told the audience Earhart’s plane would one day be recovered. And when that happens, it will change the 87-year-old conversation about Earhart.

“Liz said this great thing on an interview she did not so long ago: Once the plane is found, it shifts the narrative from her disappearance to her life, and she was a tremendous person,” he said, encouraging the audience to read books Earhart had written. “Maybe that will bring some attention on how cool of a person and how cool her story was.”